Edward S. Curtis: The Man, The Myth, The Legend

Edward Sheriff Curtis, Sioux Chiefs, 1904. Preus museum Collection

Edward S. Curtis (1868-1952) was a determent, carismatic pioneer photographer who in 1900 set out to document the traditional lives of American indigenous people. His work was rediscovered in the 1970s and is now synonymous with photographing American indigenous.

There is little to suggest that Edward Sheriff Curtis (1868–1952), who was born in Whitewater, Wisconsin, and grew up in Cordova, Minnesota, had extensive contact with Native American tribes during his formative years. His only knowledge of the indigenous population was presumably the tales of them he was acquainted with from the press and popular culture. Even so, at the age of thirty-two he ended up embarking on the great journey of his life, with a single goal in mind: to document the indigenous peoples of North America.

The finest portrait photographer in Seattle

Edward S. Curtis, self portrait 1899

Curtis hailed from relatively humble origins. He ended his formal schooling already as a twelve-year-old, and three years later he applied to serve as an apprentice for a photographer in St. Paul, Minnesota, where he stayed for almost two years. In 1887 Curtis moved with his father to Washington state, but later that same year his father passed away. This led to financial worries for his family, and Curtis had to put his plans of becoming a photographer to the side. It was not until 1891, after his family moved to Seattle, that he would again have the chance to work with a camera. It didn’t take much time after he founded his own studio before Curtis was known as the finest portrait photographer in town. His thriving business provided him with enough leeway to pursue his passion for nature and outdoor recreation.

A new vein of photography

Two chance encounters would radically influence Curtis’s life. First, in 1895, the celebrated portrait photographer, who made his living by eternalizing the citizens of Seattle, took a series of photographs of Princess Angeline, the eldest daughter of Chief Seattle. These pictures led to a national breakthrough, and this recognition led Curtis into a new vein of photography. Then a few years later, on one of his many trips, Curtis saved a group of researchers who had gotten lost in the mountains near Mount Rainier. One of these researchers was the anthropologist George Bird Grinnell. Grinnell became a close friend and was Curtis’s mentor on his first official expedition to Alaska in 1899. This expedition, organized and led by the American railway magnate Edward Harriman, was regarded as the largest such venture of the era.

A year after the Harriman expedition, Grinnell invited Curtis to the Piegan reservation in Montana. The two journeyed together to be present at what was presumed to be the very last time the Blackfoot Confederacy would perform the Sun Dance ritual. Both the ritual and the encounter with the indigenous people made a deep impression on Curtis, prompting him to conceive of a major photographic documentation project that aimed to record the Native American population’s way of life before it was supplanted by more modern lifestyles. The same year Curtis led the first of many expeditions where, accompanied by several assistants and scientific collaborators, he began the extensive work of documenting the diverse ways of life of the North American tribes.

Through his network of acquaintances and his newfound reputation as a skilled photographer, Curtis managed to attract sponsors to back an extensive book project. In 1906 he secured a deal with the financer and banker John Pierpont Morgan, who granted Curtis a stipend of $75,000 in order for him to deliver the finished product within five years. As the story goes, Morgan, after having been persuaded to participate, wrote to Curtis that “I want to see these photographs in books – the most beautiful set of books ever published”. As the primary sponsor, Morgan would receive twenty-five sets of the book series and five hundred original photographs.

The first volume was published in 1907 and focuses on the Apache, Jicarilla, and Navaho tribes. The fact that the preface was written by none other than President Theodore Roosevelt testifies to the prestige that Curtis’s project enjoyed in the beginning. However, over two decades would elapse before the final two instalments of the twenty-volume series would see the light of day.

Edward Sheriff Curtis, The Vanishing Race, 1904, Photogravure, Preus museum Collection

«Kill the Indian, and Save the Man»

One of the signature photographs from the first volume is titled The Vanishing Race (1904). The choice of title and subject matter was not coincidental: the small band of people from the Navajo tribe riding into a blurry landscape symbolizes how the condition of the indigenous population was commonly perceived at the time. Ever since the Europeans landed on the American continent, there were constant conflicts between the native tribes and the new colonial masters. This was a conflict that over the centuries led to the large-scale loss of both human life and precious resources. It has been estimated that epidemics that were brought to the country by Europeans, as well as wars and skirmishes with settlers, reduced the population of certain tribes by as a much as 90 per cent.

In the late 1800s, the official American policy was that the native population was to be assimilated, under the motto “kill the Indian, and save the man”. One of the measures was to ban the public performance of religious rituals. Many natives were also forcibly relocated from their ancestral homelands, and many tribes were coerced into reservations. There was a deliberate policy of inducing the tribes to abandon their culture and their own language. Many children were therefore separated from their parents and placed in boarding schools. The goal was to tame the “savage Indian” and educate him to become a good, civilized citizen of the modern America.

«The North American Indian»

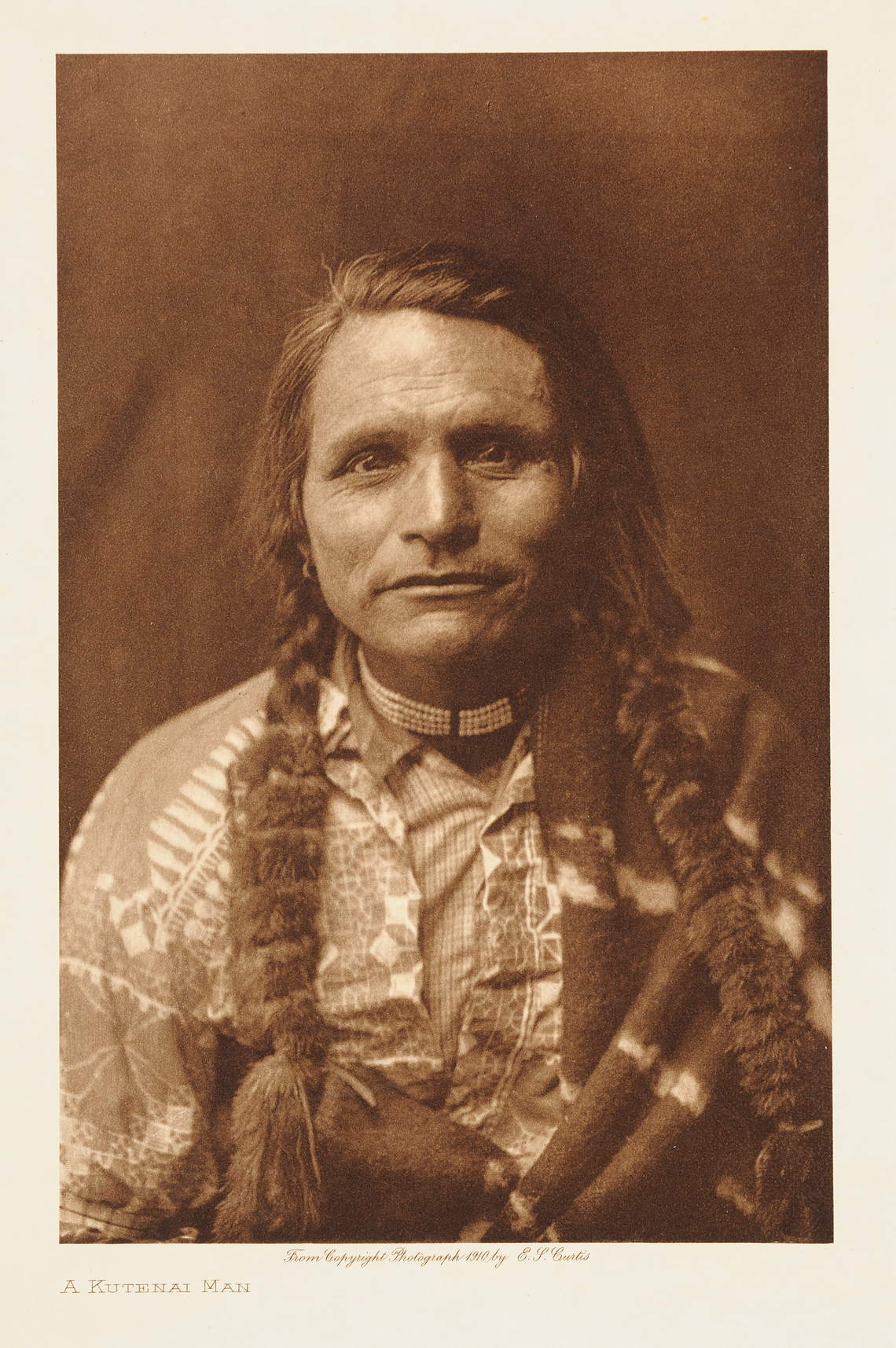

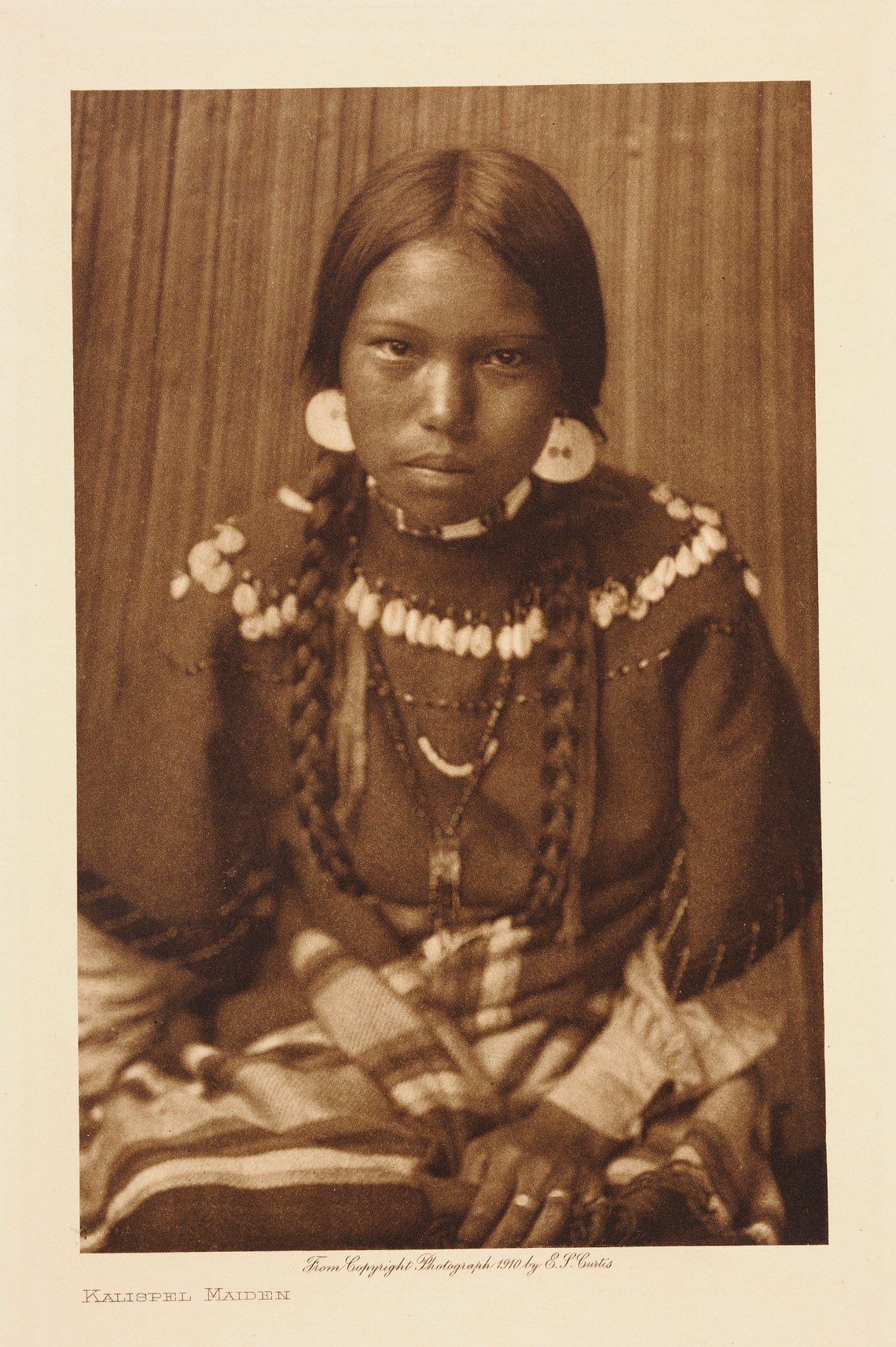

By the end of his journey, Curtis and his team had produced around 40,000 photographs, over 10,000 audio recordings, and a feature film. The twenty-volume work The North American Indian contains 1,506 illustrations presented side by side with 4,000 pages of ethnographical text. In addition, a selection of 722 photographs were sold in portfolios, or as standalone, famed photographs, all of which were produced with meticulous craftsmanship and used premium techniques such as photogravure, platinotype, and orotone positives on glass plates.

Edward Sheriff Curtis, Pipe – Stem – Oto, 1927, photogravure, Preus museum Collection.

The most famous of these images clearly evince Curtis’s aesthetic vision and artistic motivation. He created heroic portraits and poetic depictions of the indigenous population’s daily life and rituals. The pictures embrace a pictorialist style with painterly and atmospheric elements, in line with the ideals of the era’s art photography, even as several of the photographs are influenced by a “straight” photographic gaze. On his expeditions, Curtis also depicted what he saw and the people he encountered. This provides us with historical documentation that does not merely reproduce clichés and conventional ideas. There are for example many photographs of dwellings and ways of life adapted to the regional conditions the various tribes faced.

Curtis’s popularity did not hold sway throughout the thirty years it took to finish the project. Despite the financial support from sponsors and his early success, the work would leave his life in ruin. By the time the final two volumes were published in 1930, the United States was being rocked by the Great Depression. His pictures had fallen out of fashion and were no longer commercially viable. Curtis himself went bankrupt, became divorced, and suffered from poor health. In order to survive he had to work as a still photographer in Hollywood.

A controversial legacy

For around forty years, The North American Indian was overlooked and forgotten. It was not until the 1970s that Curtis’s work was rediscovered and given a prominent place in the history of photography. Today, his photographs are on copious display in many American and European cultural institutions, but his legacy has been debated. It has emerged that several of Curtis’s photographs were staged and that signs of contemporary American life, such as watches, umbrellas, and modern clothing, had deliberately been omitted. This has led to criticism and damaged Curtis’s standing as an ethnographic photographer. Moreover, his photographs have been accused of portraying Native Americans in a one-dimensional, romanticized, and nostalgic way, with some critics contending that the images had no basis in contemporary life but instead mirror a way of life that had long since become obsolete.

But these views are far from unanimous. When the photographs are reinserted in their original context and linked to written documents, audio recordings, and living pictures, they become a vital source of history. For that reason, many Native Americans also recognize the importance of Curtis’s legacy as a significant contribution to the story of their ancestors, traditions, and particular identity.

Curtis's horizon

Ellisif Wessel, Norwegian mountain lapps by their camp west of Langfj., 1910. Preus museum Collection

Photographs are not created in a vacuum but relate to their day and age. What sort of ideas were current when Edward S. Curtis worked on his magnum opus?

We humans are curious about other humans. The history of photography is full of examples of this phenomenon, showing the diversified and beautiful – but sometimes also uncomfortable – result of wanting to capture people in a photograph.

During the second half of the nineteenth century, travel photography went hand in hand with early ethnographic photography. What both genres had in common was an interest in presenting lifestyles from other cultures.

Many of the journeys were carried out in the spirit of colonialism, something that also had serious repercussions. Using anthropometry (the scientific study of measuring the human body and its proportions), some researchers developed pseudoscientific methods for classifying people according to race and type. In this context, photography became a key tool for shoring up the ideology of the divide between the superior white race and “the others”. The photograph was considered to be a more objective and true depiction and devoid of human interpretation, something that fit well with the contemporary emphasis on the objectively measurable.

In the Nordic countries as well, there was an interest in “the others”. In the Norwegian context it was the Sámi people who were photographed. Portraits of the Sámi population from the late 1880s, taken by the Danish aurora borealis researcher Sophus Tromholt (1851–96), have been the particular focus of attention because these photographs seem more personal than other “Sámi pictures” from this time. The portrait sitters are named, and viewers perceive them more as individuals than as the representatives of a particular group. Writer and author Ellisif Wessel (1866–1949), who lived in Norway’s northernmost region Finnmark for large parts of her life, chose to photograph the Sámi population and their dwellings in a sober, documentary style. Both these directions are also evident in Curtis’s work.

Norwegians also travelled abroad in order to study “the others”. One of these researchers was the ethnographer and explorer Carl Lumholtz (1851–1922), who studied the peoples of Mexico, Australia, and Borneo. Lumholtz was an international luminary and his works have been published in several languages, such as his 1920 book Through Central Borneo: An Account of Two Years’ Travel in the Land of the Head-hunters between the Years 1915 and 1917, which also included numerous photographs.

From the left photograph by: Hans Maartmann, Negretti&Zambra, Per Solem Pingo, Nils Torgersen Aastad, 1880-1991. Preus museum Collection

At the same time that photography was a handy medium for presenting “the others”, it also became common for people to go to a photographer to have their own picture taken. These small calling card portraits were collected in albums, often together with pictures people bought of celebrities or of exotic locations. Thus, a dear aunt or uncle could be end up in the album side by side with an Australian Aborigine.

As in painting, studio photographs used props to present the sitter in a certain way. The backdrop could be painted with scenery from a certain landscape, a house, or beautiful architecture. This is a style we recognize from the genre of folk costume pictures that was in vogue in early-nineteenth-century engravings and drawings. The typological gaze that was evident in these images changed somewhat during the transition to photography. As viewers, we know that a photograph shows an actual person who has sat for the picture, and this affects our perception of the picture – we interpret it with greater focus on the individual. This is for example something we experience with the mid-nineteenth-century photographs of Norwegian folk costumes taken by the Danish photographer Marcus Selmer (1818–1900).

When encountering Curtis’s photographs as well, viewers may feel that the sitter comes clearly into view. How we as viewers understand this experience will vary. For a Native American, the photograph may represent a beloved memory of a distant ancestor, or it may be experienced as an offensive objectivization of their own history.