The world in 3D

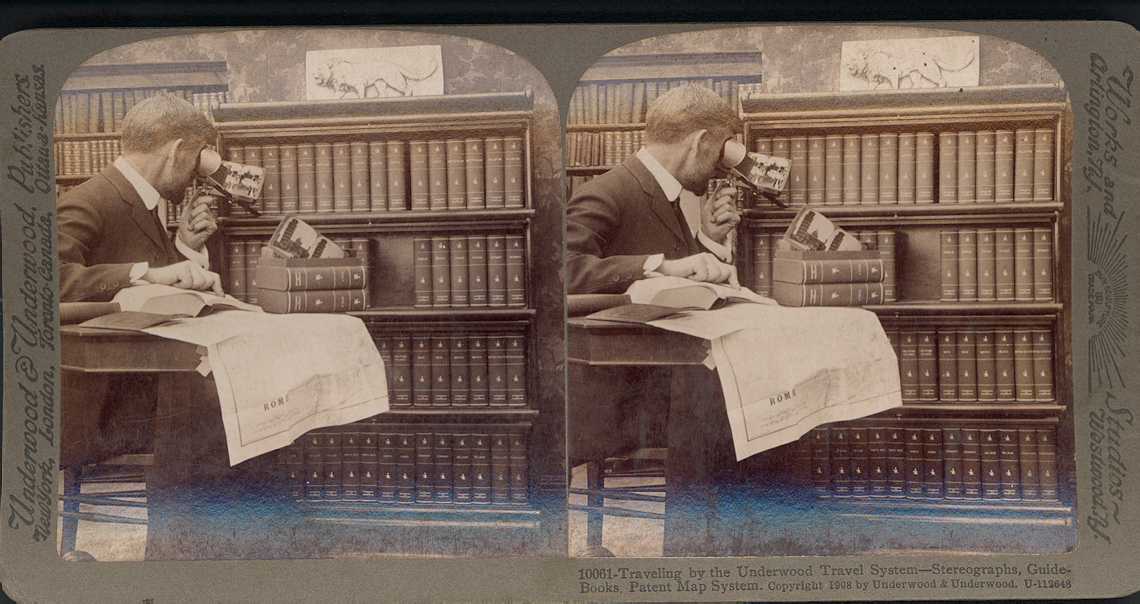

Underwood & Underwood (unknown photographer), Gudvangen's outlook over the Nærøfjord where the sea reaches far in among the mountains, Norway, 1905. Stereo Photograph. Preus museum Collection

Although photographs are two-dimensional in their form and lack the third dimension, namely the sense of depth, several different techniques for achieving such a sense of depth have been developed over the years.

Our eyes are placed roughly 65 mm apart from each other. This slight divergence entails that the brain receives two images of the world from two slightly different angles. This crucial quality allows us to judge distances and how objects are placed in relationship to one another. Although photographs are two-dimensional in their form and lack the third dimension, namely the sense of depth, several different techniques for achieving such a sense of depth have been developed over the years.The most common technique is stereoscopy, where a device of some kind makes two near-identical images be seen as one.

Holmes Stereoscope, production period 1861 - this date. Preus museum Collection

Another technique is so-called anaglyph 3D, where two images in the complementary colours red and cyan, which is a bluish-green hue, provide a three-dimensional picture in more or less black-and-white. (Unfortunately, this technique will not feature in the present exhibition.)

A third technique creates raster pictures or lenticular pictures, not all that unlike pictures with a plissé effect that are also based on multiple images. What all these techniques have in common is the idea of tricking the viewer into seeing two-dimensional images as three-dimensional, or, in the case of lenticular pictures, into recognizing images in a three-dimensional installation.

The oldest book in the Preus Museum library is about precisely the eye and depth perception. The book is from 1505 and is the first printed edition of the works of the mathematician Euclid (ca. 325–ca. 265 BC), as translated from Ancient Greek to Latin by the Venetian humanist Bartolomeo Zamberti (1473–1543). Ever since the Renaissance, researchers from many different disciplines have been interested in eyes, vision, perception, and illusion. While the German physician Georg Bartisch (1535–1607) was primarily interested in the eye’s physical condition and in cures for defects and ailments, Gaspar Schott (1608–66) was a researcher who published many works on a wide array of fields, including experiments within optics and acoustics.

Hand colored stereo daguerreotype, photographed between 1841 and 867. Preus museum Collection

In 1838, shortly before the invention of the daguerreotype, the Englishman Sir Charles Wheatstone (1802–75) invented the mirror stereoscope. By drawing two similar pictures of an object and placing two mirrors between them, he obtained a set of mirror images that could be seen by an eye on each side. It was difficult to create pictures of people and landscapes that could be seen three-dimensionally, but the invention of the photograph made this possible. The Czech Ludwig Moser (1833–1916) produced stereoscopic photographs that were made public in 1844. The same year the English researcher Sir David Brewster (1781–1868) replaced the mirrors with prismatic lenses, which made the stereoscope far more functional. Brewster is a central figure in the early history of stereo photographs. His research on light improved British lighthouses and led both to the invention of the kaleidoscope and to a proposal for a stereo camera with two lenses. He was so excited by the stereo effect that he sent stereoscopic pictures and viewers to several well-known people, since the interest in stereo photography was not all that great in the beginning. The Great Exhibition held in 1851 at the Crystal Palace in Hyde Park, London, marked a surge in public interest, in particular after Queen Victoria showed her enthusiasm. Over one thousand Brewster stereoscopes were sold the first year. Several photographers, such as Antoine Claudet (patent 1853), William Edward Kilburn (patent 1853), and John Stull (patent 1855), attempted other solutions, but with the invention of the wet collodion process the motto soon became “no home without a stereoscope”.

Brewster is a central figure in the early history of stereo photographs. His research on light improved British lighthouses and led both to the invention of the kaleidoscope and to a proposal for a stereo camera with two lenses. He was so excited by the stereo effect that he sent stereoscopic pictures and viewers to several well-known people, since the interest in stereo photography was not all that great in the beginning. The Great Exhibition held in 1851 at the Crystal Palace in Hyde Park, London, marked a surge in public interest, in particular after Queen Victoria showed her enthusiasm. Over one thousand Brewster stereoscopes were sold the first year. Several photographers, such as Antoine Claudet (patent 1853), William Edward Kilburn (patent 1853), and John Stull (patent 1855), attempted other solutions, but with the invention of the wet collodion process the motto soon became “no home without a stereoscope”.

Brewster stereo viewer, around 1850. Preus museum Collection

The first camera dedicated to stereo photography, namely a camera with two fixed lenses, was constructed by the English optician John Benjamin Dancer (1812–87) and patented in 1856. This camera can be seen in the museum’s exhibition on the history of photography.

The fascination for three-dimensional photography has lasted until the present day. Many of the camera models were produced for several decades. The French Richard Verascope was introduced in 1884 and was for sale all the way until the 1930s. With simple and inexpensive stereoscopic viewers, stereo photography gained widespread popularity. People could buy series about for example the First World War battlefront or travels to exotic locations.

Stereo photographs: how to create them

The image is photographed from two different viewpoints with a slight lateral shift between them, typically 6–7 cm or so (corresponding to the distance between the eyes) or else somewhat more in order to accentuate the sense of depth, for example to remove landscapes. Cameras that are constructed for stereo photography have two lenses. The developed pair of pictures are viewed through a stereoscope, for example the famous View-Master, which was used among other things to see images culled from Disney’s animated films from 1940 on. The stereoscope makes the two images blend into one, thereby creating a sense of space. The images can also be projected and seen through glasses or through differently coloured glass.

Ever since Brewster first published his 1856 book The Stereoscope: Its History, Theory and Construction, manuals on how to take the best stereo pictures have been published. Today, a useful Norwegian-language website for people interested in stereo photography can be found at https://www.stereofoto.no. An important prerequisite for taking good stereo pictures is that the foreground stands out against both the middle ground and the background so that the sense of spatiality is clear. Countless firms and private individuals created stereo pictures in the late nineteenth century and early twentieth century.

Underwood & Underwood

Produced by Underwood & Underwood Publishers, Gigantic Lilly leaf (Victoria Regia), used as raft-in charming Como Park St. Paul. Minnesota, 1905. Preus Museum Collection

m of Underwood & Underwood was founded by two brothers in 1881. At its peak, the firm was the world’s largest manufacturer of stereoscopic pictures with a production of over 10 million a year and texts in several languages. Despite this success, the company sold its stereoscopic division in 1920 to the Keystone View Company, which then continued making some of the same pictures and also began their own production. The letter V before a number indicates that the negative originally hailed from Underwood & Underwood.

Several private archives at Preus Museum

Stereoscopic photography has been particularly important to amateurs with relevant professions who benefit from using the illusion of space in this type of picture. The museum’s collection consists of a few acquisitions as well as donations from heirs.

Hans Grendahl (1877–1957) graduated as an architect in 1902, before travelling to the technical college in Karlsruhe, Germany, for further education. His employment history includes a stint at the firm Jacob Digre in Ålesund in Western Norway, before he moved to Trondheim and became an assistant teacher in construction and drawing at the technical college there. In 1916 he was hired as a teacher at the Norwegian Institute of Technology (today’s NTNU in in Trondheim).

Grendahl understood that stereoscopic photography afforded a unique opportunity to convey a sense of space. He left behind an exceptional archive of photographs from the 1920s and 1930s that was transferred to the museum in 1989. This archive consists of 1,017 photographs on glass plates in the 90 x 140 mm format. The pictures, in both colour (the autochrome process) and black-and-white, feature interiors and exteriors of churches and other buildings in the regions of Trøndelag, Gudbrandsdalen, Østerdalen, Møre og Romsdal, and Telemark.

Birger Wilhelm Due (1877–1951) took his middle school exam in Fredrikstad in 1894. Shortly thereafter he left for Germany, where he trained as a decorator. In 1902 he opened a workshop for decorative painting, theatre decorations, banners, and advertising posters at Bingsgaten 22, before founding a paint and painting shop at Tvergaten 1 two years later. Due was a member of the Fredrikstad city council and the chairman of the local painters’ guild, and in 1917 he became the first chairman of the board for the cinema in Fredrikstad.

As a painter, decorator, and film enthusiast, he understood the challenge of stereo photography. Several of the photographs from his family’s country estate or from travels reveal a distinct ability to create compositions that became truly eye-catching when seen through a stereoscope. Many pictures are from the family’s country estate Kringsjå, located in Foten in Øyenkilen outside of Fredrikstad.

Lenticular pictures

Lenticular prints or lenticular printing is a technique for creating a type of image that changes when seen from different angles. A lenticular picture gives the impression of depth or movement. The picture consists of several images that have been divided into stripes and covered with a plastic layer of lenticular grooves.

3D film

The first 3D film was shown in New York in 1915. The creators used the anaglyph process where spectators had to use glasses with red/blue foil lenses, a process that was best suited for black-and-white films. Throughout the 1920s, a number of feature films were made with this technique, even as other methods were tried out. It is during this time that the concept “3D” became commonplace. In order to coax viewers back to the cinemas after the Second World War, a host of 3D films were produced in the 1950s.

The first of these films was Bwana Devil in 1952, written, directed, and produced by Arch Oboler. It was filmed with natural 3D (dual-strip 3D) and with the Ansco Color process. The narrative is based on a true story from Kenya, where the construction of a railway was disrupted by two human-eating lions that threatened the workers, prompting the British leader to hunt the lions down before more workers were killed.

Arnold Johansen

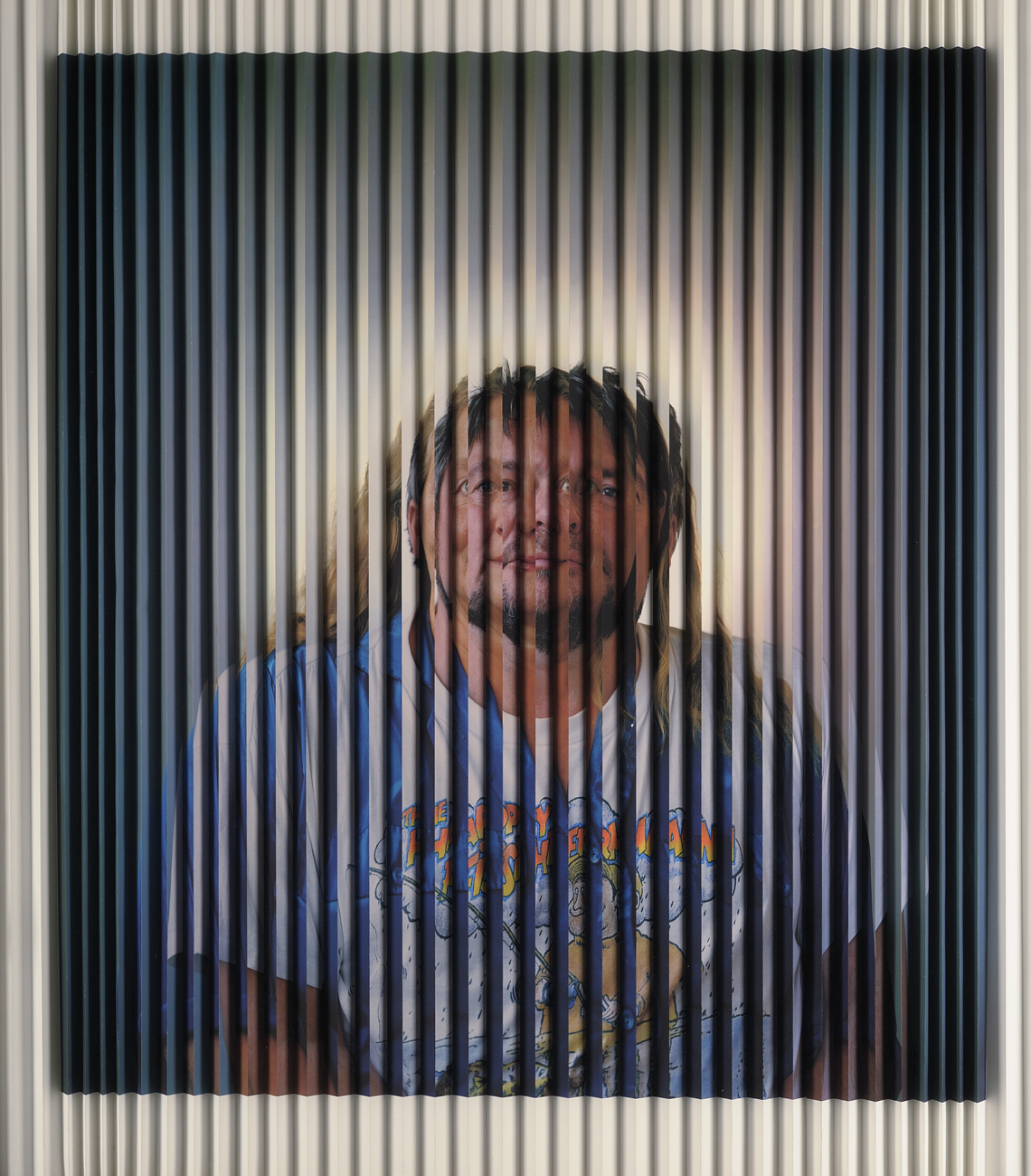

Arnold Johansen (b. 1953) calls his works “folded” or “striped” pictures, which are made in the same way that Gaspar Schott describes in his book from 1657. The pictorial plane has been composed in such a way that we see three different images, namely from the sides and the front; the picture thus changes as we move about in front of it.

The folded pictures invite the viewers to reflect on how multifaceted we ourselves are as humans. The same can be said about the small altar, where the pictures of the event and of the protagonists encourage a form of religious/Christian reflection and prayer.

Sebastian Sanders

The three-dimensional paper objects made by Sebastian Sanders (b. 1969) create an illusion that shifts between surface and perspective, not unlike the technique that stereoscopic photographs or lenticular pictures are based on.