Wall of Fame/May: Edward S. Curtis

Edward S. Curtis, Sioux chiefs, 1904, Photo gravure. Belongs to the collection of the Preus museum.

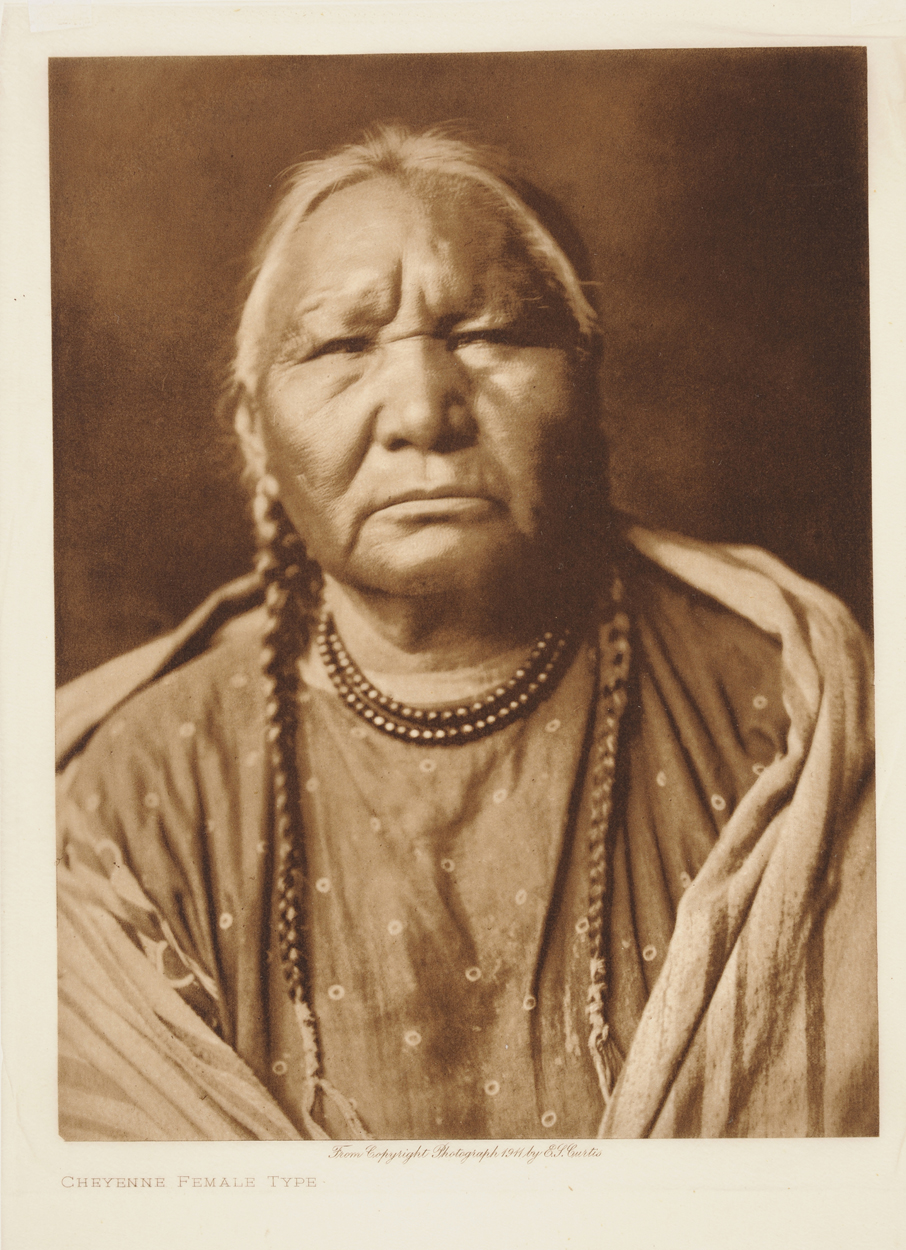

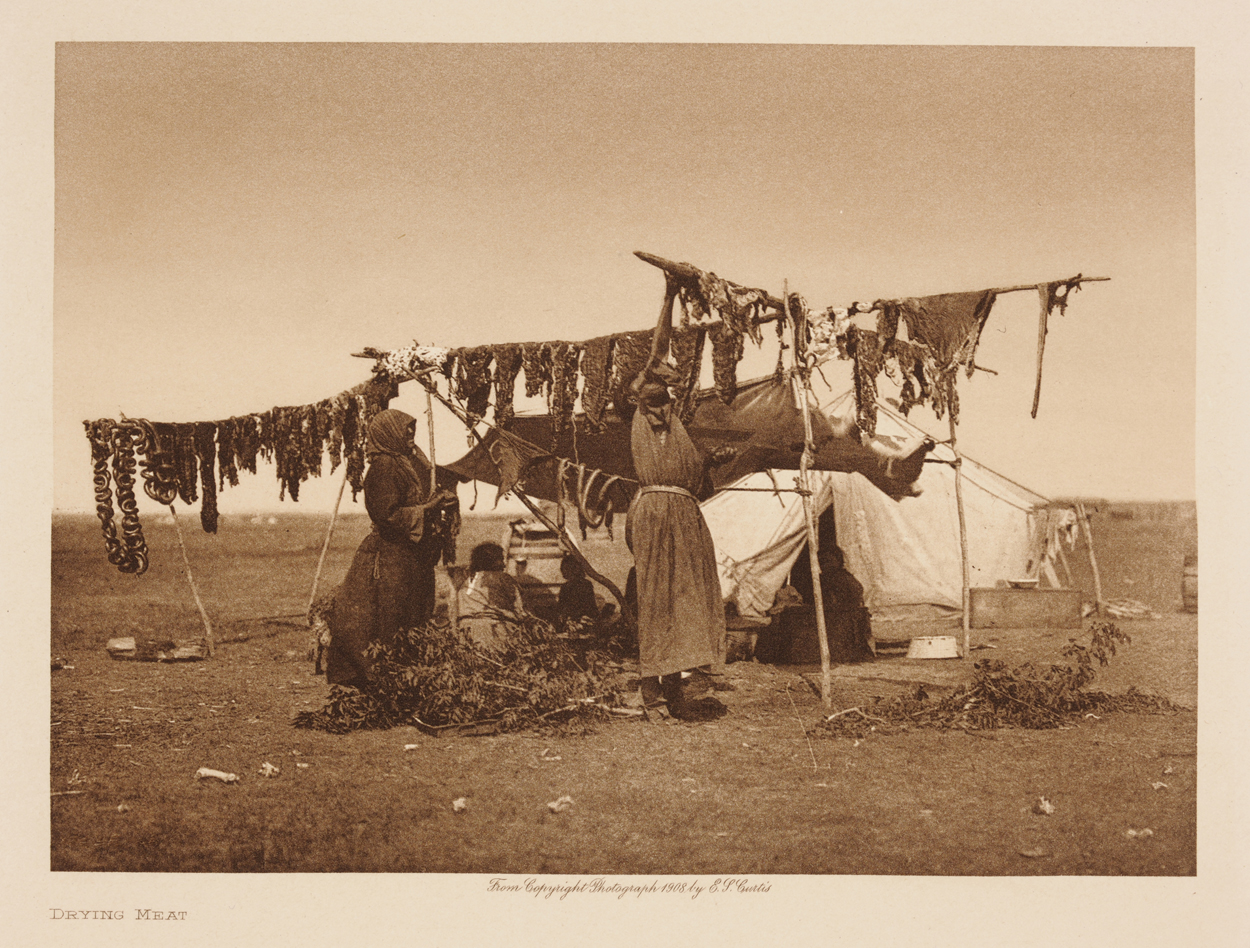

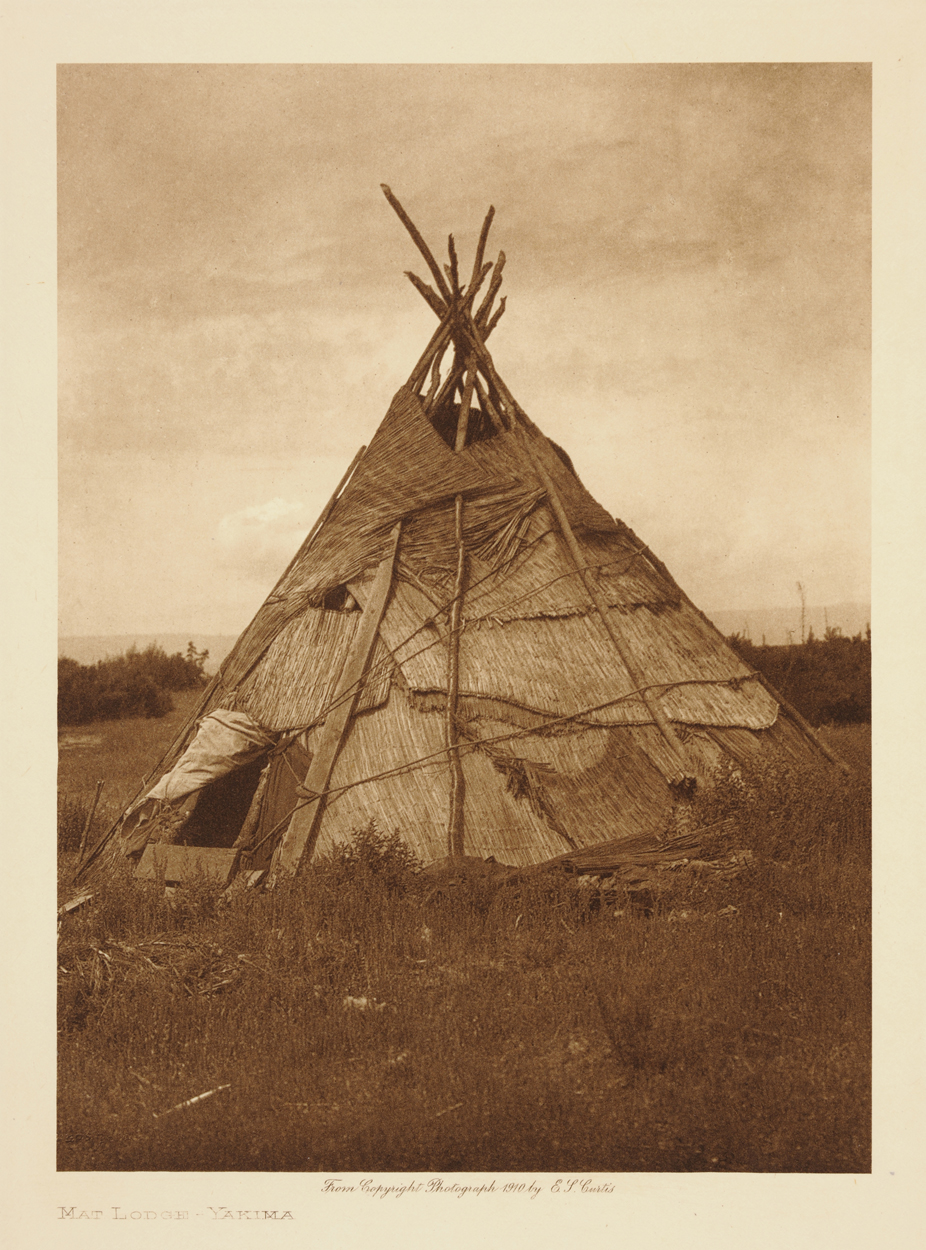

Every month a new photograph is presented on the «Wall of Fame» - the innermost wall in the anniversary exhibition From Vision Machines to Instagram. Edward Sheriff Curtis (1868-1952) devoted himself to photographing a dying culture, the North American Indians.

Curtis was born in Wisconsin, his father a priest and later a businessman. In 1874 the family moved to Minnesota. Curtis left school after the sixth grade and built his own camera. In 1885 he began as an apprentice to a photographer in St. Paul, and when the family moved to Seattle in 1887 Curtis bought a new camera and became a partner in the studio of Thomas Guptill.

In 1895 Curtis photographed his first portrait of an American Indian, Princess Angeline, daughter of Chief Sealth of Seattle. In 1898 he met a group of researchers led by anthropologist George Bird Grinnell, and the following year Grinnell and Curtis participated in an expedition to Alaska. Curtis was again requested by Grinnell to join an expedition to photograph Blackfeet Indians in Montana in 1900.

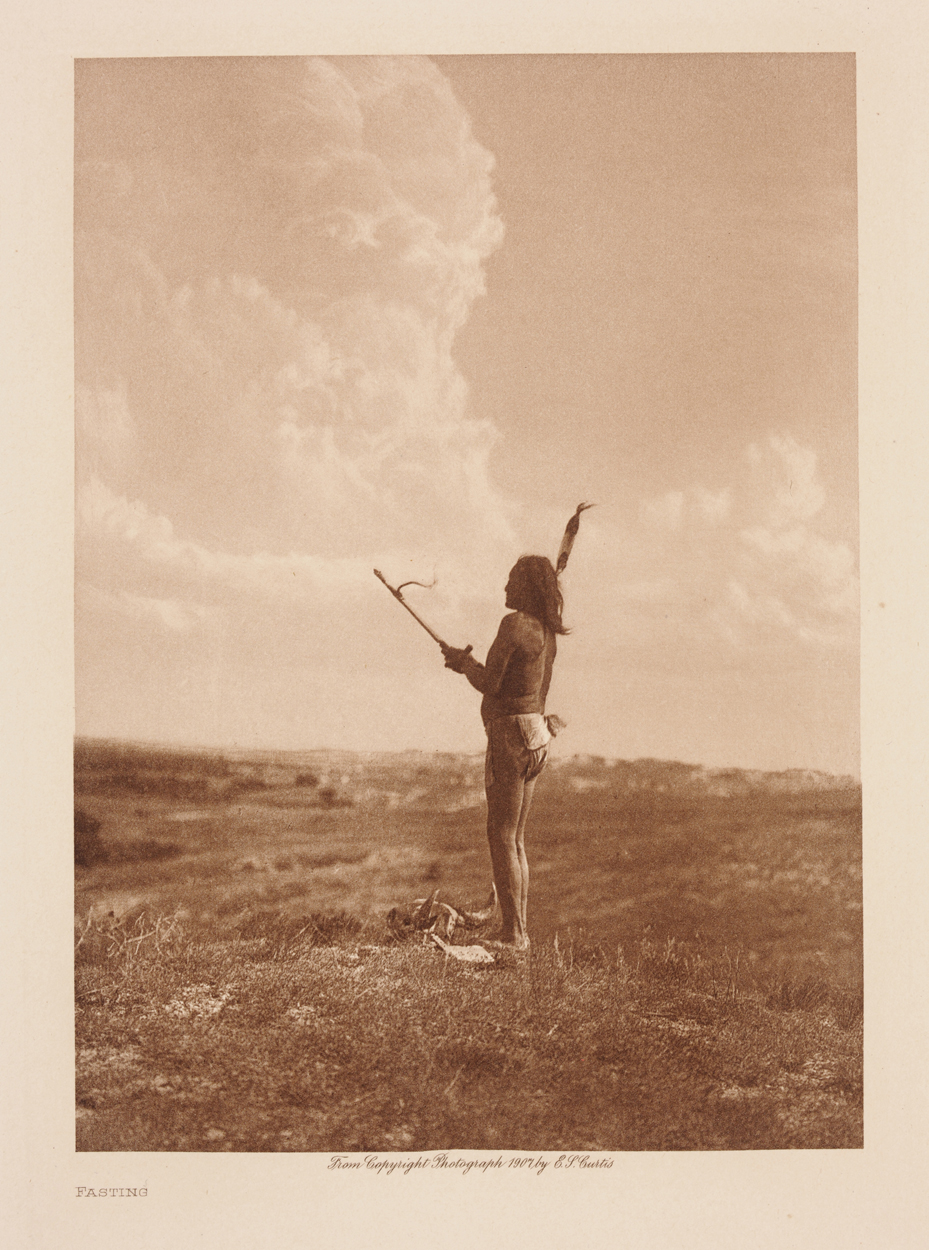

Edward S. Curtis, Crazy Thunder - Ogalala, Photo gravure, 1907. Belongs to the collection of the Preus museum.

In 1906 Curtis received an offer from financier J. P. Morgan to fund a series of books about the North American Indians. As payment Morgan was to receive 25 sets and 500 original photographs. The plan was to produce 20 volumes including a total of 1500 photographs.

Curtis's goal was not only to document but also to portray a culture he saw to be dying. Although he was not part of the Pictorialist movement, he drew inspiration from that stylistic direction, which was dominant at the beginning of the 1900s. In this way he communicated his respect, but was also viewed with skepticism by some because he partially staged his pictures.

Curtis married in 1892 but was divorced in 1919. His wife took over the studio in Seattle with all equipment, and around 1920 Curtis moved to Los Angeles, where for a time he worked as an assistant cameraman for Cecil B. DeMille. In 1928 Curtis sold the rights to the entire project with J.P. Morgan to Morgan's son, and in 1935 the material was sold again to Charles E. Lauriat's Boston firm, which bound everything that was still loose. The remainder was then forgotten in a cellar and not found before 1972.